For a man whose very name represents an entire era of film comedy, Mack Sennett has managed to remain in the shadows of his own legend. A pioneering film producer with over one thousand films to his credit, Sennett is perhaps best known for establishing Keystone Studios in 1912, the home of the famed Keystone Kops and the training ground for many of early film comedy's greatest comedians. Brent E. Walker's new book on Sennett and his studio, Mack Sennett's Fun Factory, sets out to distinguish the historical facts from the myriad of apocryphal stories surrounding Sennett by looking beyond the stereotypical views of his work -- epitomized by those iconic airborne pies -- in the process effectively re-evaluating his cinematic output on its own terms.

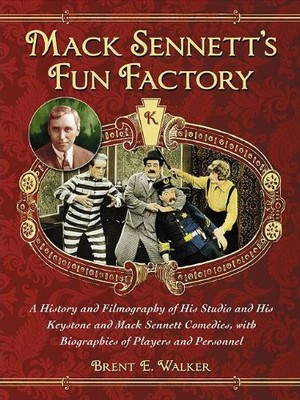

Dubbed "The King of Comedy," Mack Sennett earned that title by employing (and often establishing) such notables as Charlie Chaplin, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, Mabel Normand, W.C. Fields, Charley Chase, Harry Langdon, and many others. A figure as towering and prolific as Sennett deserves an equally massive study, and Mack Sennett's Fun Factory is indeed massive, a weighty hardcover of over 600 pages which contains nearly 300 rare photographs. Organized into three distinct sections, Walker's volume is essentially three books in one: a thorough history of the Sennett studio; a meticulously researched filmography; and an encyclopedic overview of the various on-screen and behind-the-scenes talent who had worked for Sennett.

The initial section of the book provides a lucid history of Sennett's entire career, covering his apprenticeship at Biograph under the guidance of D.W. Griffith, the Keystone years (1912-17), his post-Keystone "Mack Sennett Comedies," and his studio's last gasp in the early talkie period before finally closing in 1933. Throughout, Walker documents Sennett's business decisions, the comedy craftsmen who marched in (and out) of the King of Comedy's door, and, of course, the films themselves. Eschewing oft-repeated yet misleading depictions of Sennett's work as primitive knockabout, Walker emphasizes how Sennett's comedies were groundbreaking films which advanced a burgeoning art form, from their melodramatic parodies and outrageous gagging to their innovative trick photography and deftly executed sequences of comic mayhem. Sennett's effort to stay afloat during the talkie era is treated with a discerning, sympathetic eye, his studio's bankruptcy in 1933 more a consequence of the changes the film industry underwent during the Depression than of problems with the sound medium itself. Throughout the book, significant films and gags are often outlined in great detail, which is particularly useful considering that many of these comedies are, unfortunately, largely unavailable for viewing by the general public. Perhaps most importantly, Walker's tome celebrates the unsung heroes in the Sennett story -- such as comedians Billy Bevan and Ben Turpin, as well as directors F. Richard Jones and Del Lord -- talented comic practitioners who took the Sennett films (and film comedy itself) to new, gloriously absurd heights.

The book's final two sections exemplify the enormity of Walker's achievement. Part two of Mack Sennett's Fun Factory is an exhaustive and authoritative filmography, one which makes all earlier Sennett filmographies obsolete. This is especially impressive considering that Sennett's Keystone shorts were released without cast or production credits, and thanks to Walker's remarkable detective work, the book's filmography manages to correct a great deal of errors and incorrect assumptions which had marred earlier filmographies. More than simply providing cast credits, Walker's filmography details the plots and gags of surviving comedies as well as filming dates, working titles, and other useful pieces of information. The final section is comprised of brief biographies of many Sennett players and personnel, an essential reference that reveals much more about the many personalities of the Sennett lot -- most of whom have been long overlooked -- than had been previously available. Additionally, in the wake of his book's publication, Brent Walker has launched a supplementary blog where he posts material related to Sennett and his studio as it comes to light.

Fans of Charley Chase will find much of interest here, Keystone having been the site of the comedian's formative years as a performer and a developing film director. Significantly, Walker corrects Gene Fowler's dubious assertion -- in his early, print-the-legend biography of Sennett, Father Goose (1934) -- that the young Charles Parrott was one of the original Keystone Kops. Parrott, in fact, had only joined Keystone in 1914, after the Kops had already made their screen debut. Moreover, the filmography in Mack Sennett's Fun Factory serves to clarify Parrott's involvement in the Keystone films; among other crucial tidbits, Walker notes that Parrott's earliest known directorial assignment took place in May 1915, either on A Hash House Fraud or Syd Chaplin's A Submarine Pirate (Parrott seems to have directed a number of scenes for the latter film without receiving credit.)

Over twenty years in the making, Brent Walker's magisterial Mack Sennett's Fun Factory is the most extensive and most historically accurate treatment of Sennett's influential studio to date. It is both an invaluable reference source and a compelling read, one which looks past the tall tales of Fowler's Father Goose and Sennett's autobiography The King of Comedy (1954) to uncover the actual inner workings of the fun factory that, more than any other, shaped the evolution of America's comedy film industry. Mack Sennett's Fun Factory will undoubtedly remain the definitive study for years to come.