Much beloved by connoisseurs of early film comedy, Lloyd Hamilton has long been a neglected figure in most histories of the era. While Hamilton had appeared in more than 250 films across two decades, a studio fire after the comedian's death destroyed many of the original negatives of his films. As with his contemporary Raymond Griffith, Hamilton's legacy is blighted by the loss of many of the films from his peak period. The films that do survive -- particularly short comedy gems like The Movies (1925), Nobody's Business (1926), and Move Along (1926) -- reveal a gifted and highly idiosyncratic comedy mind. Most successful in short two-reel comedies, Hamilton was uniquely regarded as a "comedian's comedian," having collaborated with Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle and Charley Chase and praised by one-time rivals Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton.

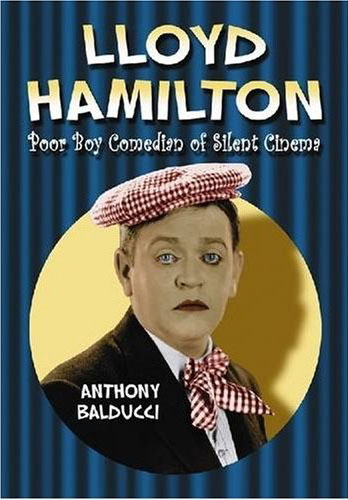

Anthony Balducci's new biography of Lloyd Hamilton is the first in-depth study of this often overlooked silent comedian, one which charts both the highs and the lows of Hamilton's film career. Raised in a conservative middle-class family, Hamilton nevertheless caught the acting bug, and after a stint performing in theatrical shows in his native California, the actor entered the fledgling film industry. Hamilton's initial success as part of the duo "Ham and Bud" is detailed at length in the book's early chapters. Paired with the pint-sized Bud Duncan, the "Ham and Bud" comedy shorts are marked by an alternately brilliant and uninspired vulgarity, yielding an inconsistent output that was undeniably borne out of a relentlessly demanding release schedule (this reviewer refers you to their classic The Sauerkraut Symphony [1916] as an example of the team at their very best.) One of the book's chief merits is Balducci's discussion of Hamilton's gradual transition from the early, crude "Ham" to his more mature alter-ego of the 1920's -- he of the checkered cap and duck-walk -- the subtler, more humane persona on which his reputation now rests. Balducci's biography reveals Hamilton to have been a performer with a keen and sensitive comic mind, and the book features many of the comedian's own thoughts on comedy and filmmaking originally published in trade magazines, interviews, and studio press releases.

The book details Hamilton's association with many of the most significant figures in the comedy film industry of the 'teens and '20s, including Mack Sennett, Henry Lehrman, Jack White, and Charley Chase, each of whom Hamilton had worked with (or for) during his career, and all colorful characters in their own right. Chase, in particular, is singled out as a comedian on whom Hamilton was massively influential, Balducci citing Billy Gilbert's oft-quoted remark, "when [Chase] played a scene he always thought, 'How would Ham play this?'" (91). While Chase (then still Charles Parrott) had only directed two of Hamilton's comedies -- April Fool (1920) and Moonshine (1921) -- the two became close drinking companions and would remain lifelong friends. As Balducci notes, Chase would often lend Hamilton money during his lean years in the 1930s, and was in attendance at Hamilton's funeral in 1935.

Lloyd Hamilton's short comedies are often afforded perceptive analysis throughout the biography, but Balducci's lengthiest treatment of a single film is his discussion of Hamilton's unsuccessful feature film A Self-Made Failure (1924), which does not survive. The feature's failure is explained through a meticulous examination of the film's script, surviving still photos, and by an effective comparison with the more successful feature-length comedies released by Keaton and Harold Lloyd during the same year. Balducci positions the beginning of Hamilton's descent as coincident with the comedian's failed feature-film attempts in the mid 1920s, an artistic and moral decline exacerbated by Hamilton's longstanding drinking problem. Balducci does not shy away from Hamilton's incapacitating alcoholism, and the later chapters of the book present his financial and emotional woes in rather excruciating detail.

The biography contains a great deal of rare photographs of Hamilton on and off screen, many of which come from the private collection of the surviving members of the comedian's family. The book also boasts three appendices, including a thorough filmography with plot summaries, blurbs from period reviews, and references to archive holdings when available. While the book is not completely devoid of minor inaccuracies -- a Harry Langdon feature film is erroneously referred to as Short Pants -- such gaffes are few and minor indeed, for on the whole, the biography is exceedingly well-researched, particularly when focused on Hamilton's own work. Most importantly, Balducci makes a convincing case for Hamilton's prominent place within the history of film comedy and his enduring influence on later comedians (Jackie Gleason was a major fan). Overall, this long-overdue biography illuminates the life and career of a talented comic innovator who has remained obscure for far too long, encouraging further analyses of his work in the future and, with any luck, the recovery of more of the comedian's elusive films.